From House League to Travel Teams: Aidan Rioux’s Hockey Evolution Story

The pathway from recreational youth hockey to competitive travel teams requires athletes to navigate complex developmental stages while adapting to increased physical demands and strategic complexity. For Aidan Rioux, a 19-year-old forward currently competing in the USPHL Premier division, this progression involved geographic relocations, skill refinements, and systematic advancement through multiple hockey systems across two countries.

Rioux’s hockey evolution demonstrates how players transition from foundational programs to elite competition levels. His journey from California house league hockey to Canadian junior systems illustrates the developmental challenges facing American players seeking advancement opportunities in competitive hockey environments.

Foundation Years in Anaheim Youth Hockey

Rioux’s organized hockey career began within the house league system at the KHS arena in Anaheim, California. House league programs provide introductory team experiences without the travel commitments and competitive pressures associated with higher-level youth hockey.

“My first organized team in youth hockey was when I played for the Junior Ducks, the KHS Junior Ducks from 2016,” Rioux explained during a recent interview. “So I was 10 years old, and that was my first organized experience in hockey. It wasn’t a travel team, it was a team, meaning we just played on our own home arena and that was it.”

House league participation functions as a developmental bridge between individual skill acquisition and team-based competition. Programs like the Junior Ducks operate as “learn to play” initiatives where young athletes develop fundamental understanding of team dynamics and positional responsibilities.

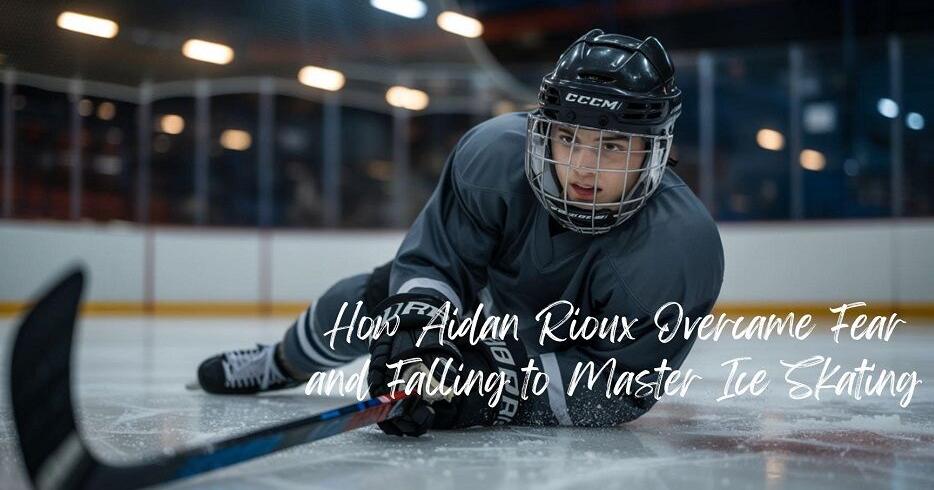

Rioux’s initial experience reflected common challenges facing new players transitioning from recreational skating to organized competition. “I really kind of struggled at the beginning, but then by my second year, the skating improved pretty drastically,” he recalled.

Skating proficiency forms the foundation for all other hockey skills, and Rioux’s development followed typical patterns where technical improvement accelerates once basic movement becomes automatic. “Once the skating is good enough where you can move around where you want to go to, then the other stuff, it’s much easier to follow along.”

Geographic Limitations and Canadian Opportunities

California’s youth hockey infrastructure presented advancement challenges for players seeking higher-level competition. Limited travel team options within the region forced ambitious players to consider alternatives in traditional hockey markets.

“In Anaheim, they didn’t have great traveling programs at the time,” Rioux noted. “You’d have to go to Canada to find some decent junior youth travel teams.”

The decision to pursue Canadian junior hockey at age 12 involved commitment to boarding arrangements and separation from family support systems. Rioux joined the Abbots Field Pilots in the PGHL, a tier two league based in British Columbia near Vancouver.

“I was put up in a boarding program basically with a building with a local family there,” he explained. Geographic relocation for hockey development requires adaptation to new living situations while maintaining focus on athletic improvement.

Canadian junior systems operate on seasonal schedules that demand extended commitments from young players. “All junior leagues are pretty much, the season starts in early October or late September and ends in March,” Rioux observed.

Four years of Canadian junior hockey provided Rioux with exposure to higher competition levels and systematic player development approaches not available in his home region.

Tier System Navigation and Advancement

Canadian junior hockey operates through tiered competitive levels that create advancement pathways for developing players. Rioux’s progression from tier two to tier one competition demonstrates how systematic evaluation processes determine player placement.

“That was tier two. It wasn’t tier one, but it was considered a junior, a tier two,” he explained regarding his initial Canadian experience. “There was a draft lottery that you do to move up to tier one, basically.”

After two seasons in tier two competition, Rioux advanced to the BCEHL, which provided AAA tier one experience at the U17 level. Advancement between tiers requires demonstrated performance improvement and evaluation by league officials who assess player readiness for increased competition.

Tier progression creates structured developmental pathways while maintaining competitive balance within age groups. Players like Rioux benefit from systematic advancement that matches skill development with appropriate competition levels.

Movement between tiers reflects both individual improvement and organizational assessment of player potential within competitive hockey systems.

Transition to American Junior Systems

Following Canadian junior experience, Rioux transitioned to American junior hockey through the USPHL system. The move involved different organizational structures and competitive formats compared to Canadian programs.

Connection with American opportunities occurred through the NCSA platform, which functions as a recruiting and evaluation service for junior hockey players. “When my profile was enlisted on NCSA, they assigned me a hockey advisor,” Rioux explained.

NCSA operates as “a platform to be scouted” where players submit video highlights and statistical information for evaluation by hockey personnel. The service connects players with advancement opportunities across various competitive levels.

Rioux’s hockey advisor provided assessment and guidance regarding appropriate competition levels within American junior systems. “He was impressed with my playing. And then I submitted some recent video highlights and he was like, yeah, I mean, you can definitely play at least USPHL, you’re right in the USPHL premier.”

The USPHL operates two primary divisions: NCDC (tier two) and Premier (tier three). Rioux’s advisor evaluated his skills as appropriate for tier three competition with potential for tier two advancement.

Current Development and Future Opportunities

Rioux currently competes with Thunder Hockey Club in the USPHL Premier division while preparing for potential advancement to higher competition levels. His development approach emphasizes conditioning and skill refinement in preparation for evaluation opportunities.

“I’m skating every day trying to play at least two pickup games every day. And yeah, also, I’m running 30 minutes every day as part of my training,” he described regarding his current preparation routine.

Recent coaching changes within his organization have created new advancement possibilities. His current coach extended an invitation to participate in tier two NCDC evaluation camps, providing opportunities to compete against higher-level players.

“Why don’t you come out in July for the tier two NCDC camp?” his coach suggested. “So you can get some reps time and compare yourself with the higher tier players, see where you stand.”

Camp participation allows players to demonstrate improvement and compete for roster positions at advanced competition levels. Rioux’s invitation reflects organizational confidence in his development trajectory and potential for continued advancement.

Rioux’s progression from California house league hockey through Canadian junior systems to current USPHL competition illustrates the complex pathways available to developing players. His experience demonstrates how geographic flexibility, systematic skill development, and strategic advancement through tiered competition create opportunities for continued improvement within competitive hockey environments.